|

Most of you reading this probably have a certain fondness for older Volvos. I've owned a lot of cars over the years with motors ranging in size from 900cc to almost 7000cc -- Italian sports cars, American muscle cars, French economy cars -- and, in my personal opinion, the only ones that really satisfy are Volvos. Old Volvos are a blast to drive and they keep running under terrible conditions -- and it wasn't like Volvo tried to keep that fact a secret, either. Today, Volvo finds itself with a 1% share of the US car market -- and that's not a lot. I sometimes wonder why there are as many old Volvos around for people like us to buy, to drive and to restore -- yes, they last a long time (pardon the ridiculous understatement), but someone must have been smart enough to buy them off the showroom floor thirty or forty years ago. Who was it?

There's an article to the contrary called "Make Your New Car Last Forever." The author takes the position that it is cheaper to keep repairing your old car than it is to trade it in, no matter what, and details his experience of keeping a '53 Chevy going for seven years and 98,000 miles (I don't know where he lived, but rust apparently was not a problem there). During those seven years, he had the engine rebuilt twice, replaced the entire exhaust system three times, ran through innumerable tires (he didn't buy them in sets), wore out a clutch and had all sorts of electrical repairs performed ( and much, much more) -- and was happy with the achievement. None of this seemed ironic to most people in 1960 -- Americans were proud of their cars; European imports were either sports models for wealthy playboys or tiny economy cars clearly unsuited to our long distances. One did not travel the length of route 66 in an Isetta, after all -- the "Saturate Before Using" bag would likely have tipped the car over on its nose. Many families developed loyalty to a particular make. In my family, that make was Ford. My uncle started this off in 1956 with a black and white Victoria, complete with "Police Interceptor" motor, automatic transmission, and power brakes and steering. He chose this car above all others because Ford touted safety features in its cars -- the only one I can remember was the dished steering wheel (which meant the steering column would spear you a few milliseconds later than in a Chevy if you T-boned a tree, I suppose). That car cost a hunk of change in those days (contrary to popular belief, cars were not cheaper then than now), and he set out to make it last forever -- in fact, it was still going when he sold it around 1990, but hadn't been in regular use for years. Anyway, my parents followed by buying a new Ford in '57. When the family needed a second car, they bought a used '52 Ford. The '57 gave way to the '61, and when that fell apart in two years, to the '63 and subsequently the '66. Such things were not considered masochistic in those days. My parents were not sporty drivers and cared nothing for things mechanical, but each new Ford had the top-of-the-line V8 under the hood. Indeed, Motor Thrift lists which options will pay you back at trade-in time -- the only thing that added as much value to your trade-in as it cost to buy new was a V8 motor. The closing irony in that issue of Motor Thrift is the final section, in which are introduced America's new breakthroughs in automotive engineering and economy: the new Chevrolet Corvair, Ford Falcon and Plymouth Valiant. I don't need to comment on this, do I? It is interesting that those cars were soon subject to horsepower inflation -- the Corvair went out after five years with a 180-horse turbocharged unit, the Valiant became the Barracuda (440 six-pack, anyone?) and the Falcon showed up in new sheet metal as the Mustang (eventually getting a 429 CobraJet motor to haul it around). But I digress. The motto of the whole Motor Thrift issue seems to be "Buy a new car with a huge motor, drive it as slowly as possible for three years, and then replace it as soon as the payment coupons run out." In my family, as old Fords became unavailable, our second cars became used VW Beetles. These were essentially disposable cars -- if the clutch started to go, you took it back to the lot and bought another one. They were dirt cheap, got you around town reliably and, as the onus of owning German-made products faded as WW-II receded, they became far and away the most common import on the roads. They were made lovable by humorous and distinctive ads in print and on TV -- how many of you remember the VW in the swimming pool? "A Volkswagen will definitely float..." -- glug, glug, glug -- "...but it will not float indefinitely."

People believed these ads ("Drive it like you hate it.") -- Volvo soon became synonymous with safety, durability, economy and performance -- but less than 1% bought one. Even Corvair, which quickly gained a largely-deserved evil reputation, outsold Volvo. What went wrong? Four things, in my opinion: 1) the Volvo was expensive. The 544 sold for several hundreds more than the Valiant (cheapest of the three "compact" cars, as they were then known), and it was targeted as competition for the Beetle (an "economy" car -- there was a difference), which was cheaper yet. The 122S cost as much as a Ford Galaxy with a big motor and power steering. Or a Valiant and a used VW. 2) Volvos did not look modern. If the 544 looked like a Ford from the '40s, the 122S might have descended from a '53 Chevy -- stylish, perhaps, but dated. The P1800 did look pretty cool in a European way, but just a few dollars more would buy you a Corvette Sting Ray straight out of some theme park's Tomorrowland. 3) Most people couldn't have cared less about making their cars "last forever." Next year's models would be even more exciting and powerful -- if NASA could launch men into orbit, who knows what General Motors might accomplish by the time your present car's seats were rusting through the floorboards. Why fight it? 4) Volvo did not advertise on TV. It's pretty hard to get your product's performance into the public conciousness when your competition shows moving pictures of their product performing, and you don't. A few short seconds of an Amazon competing in an actual rally might have gone a long way. It's just a bit more impressive than a sinking Beetle. Volvo advertising did its best to counter the first three of these problems. The cars were expensive because they were high quality -- economy does not come cheaply. If it looks old now, it won't look any more outdated in a few years, will it? The car is so far ahead of its time mechanically that it will take General Motors years to catch up (this last was true). Well, it didn't work. Americans don't decide to buy cars with their brains, they decide with their guts (and sometimes with other portions of anatomy). I saw an example of this when I worked as a farmhand in Canada in 1967. It was just a small family farm, and Bill, the farmer, had to make every penny count. He had a 1938 tractor and most of the farm machinery was adapted from horse-drawn. Every day, we loaded big cans of cream into the trunk of the car and drove seven miles over gravel roads to the dairy and back -- in a 1966 Plymouth Fury. Bill bought it because Plymouth had always been his brand of car, and the enormous Fury had a trunk deep enough to hold the cans standing up. He'd actually complain that the car had too much "pickup" -- he'd sometimes tip over a can just pulling away from a stop. For the same price, Bill could have bought a Volvo 220 wagon, produced right in Canada (Bill was patriotic and resented having to buy a US-built car). It would hold a bunch more stuff, ride better on the gravel roads, get much better gas mileage and last through a heck of a lot more Canadian winters. Bill was about sixty and didn't care a whit about how he looked, dressed or smelled, and being seen in a big car meant nothing to him. Why didn't he have a practical Volvo? One day, at the local gas station while giving the Fury a long, long drink, we spied an unfamiliar, and obviously foreign, car for sale -- a Toyota Crown. Bill spent twenty minutes inspecting it and slamming the doors over and over again. "Damn thing's built like a Rolls-Royce!" he admired, "but I'd be a blue-nosed gopher before I'd pay that dear a price for a six-cylinder." Much less a four, I suppose. Having a big car with a V8 was normal. That's all there was to it. If you didn't, you were a bit strange. Today, people drive "sport utes" -- makes just as much sense. They saw one crush a dirt clod under one of its tires on TV while a gravel-voiced announcer told them how awe-inspiring that achievement was. In 1971, gas prices in the US more than doubled, and people turned out in droves to buy four-cylinder Toyotas and Datsuns -- "Look, Pa, the damn thing's built like a Rolls-Royce!" The 240Z became the GT of choice, and Detroit spawned a race of "sub-compacts" including the Ford Pinto and the Chevy Vega; sort of the next-generation Falcon and Corvair. True to form, the Pinto soon evolved into the Mustang II (eventually stuffed with a 5-liter V8), and the Vega, mercifully, sank without a trace in even fewer years than it took the Corvair to do the same (lesson: if you're going to use an aluminum block in your motor, sleeve the cylinders). Volvo was stuck with an expensive GT, the 1800E/ES, that couldn't be made to conform to the new federal safety standards -- a very compromising position for a company that had always been a leader in the safety field -- and the 140-series, a practical mid-sized car that didn't go particularly fast or get particularly good mileage, and cost more than the Japanese equivalents. Sales dropped further. Now, would I rather own an 1800ES than a 240Z? Absolutely. Maybe I'm odd. Actually, I'm still driving the '66 122S my wife bought nineteen years ago. It has 411,000 miles on it, and there's starting to be enough rust to worry about -- mostly in the roof drip rails, though; the undercoating is still good. During the 250,000 miles that I've put on the car personally, I've had to walk home exactly once -- I locked the keys in it (yeah, there were a few roadside repairs along the way, but they were successful). Anyone know if Motor Thrift is still in business? Maybe I'll submit an article. So, to the 1% of you out there that had the sense to buy old Volvos when they were new, a large "thank you!" When you sold them at prices that people like me can afford, I hope you used the money for down payment on a newer Volvo. But if you're driving a Chevy Suburban these days, please don't tell me. |

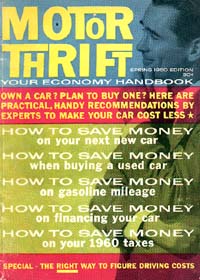

I have an interesting publication here titled Motor Thrift -- Your Economy Handbook, dated "Spring 1960". It's chock full of sensible tips on getting the most driving out of your dollars, most of which still make sense today. In retrospect, though this little book was an exercise in futility -- these people were driving around in 4000-pound behemoths that got catastrophic fuel economy, wore out a set of tires in 25,000 miles and needed major engine work at 50,000. This was academic in most cases, because the cars' bodies would usually rust through before the engines wore out. One article addresses the issue of how to calculate which will save you the most money: should you trade a new car in when it's two, three or four years old?

I have an interesting publication here titled Motor Thrift -- Your Economy Handbook, dated "Spring 1960". It's chock full of sensible tips on getting the most driving out of your dollars, most of which still make sense today. In retrospect, though this little book was an exercise in futility -- these people were driving around in 4000-pound behemoths that got catastrophic fuel economy, wore out a set of tires in 25,000 miles and needed major engine work at 50,000. This was academic in most cases, because the cars' bodies would usually rust through before the engines wore out. One article addresses the issue of how to calculate which will save you the most money: should you trade a new car in when it's two, three or four years old?

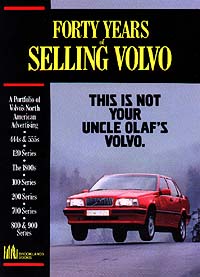

Where was Volvo in all this? It had its own North American import operation in 1956, and the advertising is entertainingly documented in Brookland Books Forty Years of Selling Volvo. Right from the start, the PV444 was billed as "the family sports car" and its impressive racing and rally achievements were listed alongside claims of 35 MPG fuel economy. Subsequent ads for the 544 and 122S retained this theme, adding claims of toughness, safety, comfort and quality as the cars and the campaigns developed. By the early '60s, Volvo ads had much of VW's humor, cuteness and graphic layout. There was no doubt that a 544 was superior to the Beetle in fuel economy, could carry much more and could run rings around it in any conditions (except, perhaps, in swimming pools), and that the 122S would do much the same to a Corvair, Falcon or Valiant.

Where was Volvo in all this? It had its own North American import operation in 1956, and the advertising is entertainingly documented in Brookland Books Forty Years of Selling Volvo. Right from the start, the PV444 was billed as "the family sports car" and its impressive racing and rally achievements were listed alongside claims of 35 MPG fuel economy. Subsequent ads for the 544 and 122S retained this theme, adding claims of toughness, safety, comfort and quality as the cars and the campaigns developed. By the early '60s, Volvo ads had much of VW's humor, cuteness and graphic layout. There was no doubt that a 544 was superior to the Beetle in fuel economy, could carry much more and could run rings around it in any conditions (except, perhaps, in swimming pools), and that the 122S would do much the same to a Corvair, Falcon or Valiant.