|

|

Mark Hershoren foreignaffairsdesk@vclassics.com It is a fairly universal desire: To be given the opportunity to revisit a gratifying experience that occurred in one's youth. Admit it. You've wished for something like this yourself one time or another. Here, then, is the story of a small group of men who have found their time machine, and with it unfolds the story of the Davy Volvo Special.

Growing up in the mid-1950s on the Niagara Peninsula, in the rural communities of Vineland and Beamsville in Lincoln County, Ontario, Don Davy and Fraser Earle were typical as teenage boys: Car Crazy. Earle had his first car by age 14 and, like many through the high school years, both he and Davy built hot rods. As young tastes in motor cars developed, thoughts turned away from hot rods and turned toward sports cars. Many had exotic sounds and sinewy lines. And they were by-and-large unaffordable, therefore unobtainable. To get closer to their desire, Davy and Earle began to frequent venues where the sports cars played. The two became regular spectators at various airport courses such as Harewood, Greenacres, Dunkirk, and also often crossed the border to visit the rural area surrounding and running through the town of Watkins Glen, New York, for those legendary events. It was at Dunkirk, however, that Davy saw his first racing specials: one-off, sometimes home-built machines that looked and performed in many cases as well or better than the manufactured cars. Borrow some of this and fabricate some of that. For Davy and Earle, it must have been a revelation. I Can Do That! The idea dawned on the two lads that maybe there was a way for underfinanced 17- and 19-year-olds to be in possession of a Sports Car: Build it. When a hapless fellow in Watkins Glen overstretched his driving ability as well as the handling limits of his brand new 544 to the point of making the car a total write-off, Don Davy was there to tender a bid of $101.00 for the rights to salvage. Typical bids of the day would be $100.00. Davy's savvy and an extra buck gained him the balled-up car. Earle's interest in automobile design and function, pooled with Davy's completion of the first year of an apprenticeship as a body man, resulted in a determination that a space-frame chassis might be the best answer to their quest. By then, the desire for a sports car was also fueled at full throttle by the succession of cutaway drawings of noteworthy marques that appeared monthly in Sports Car Illustrated and by the continued dominance of Watkins Glen by Bill Sadler. It was September of 1958. Bill Sadler hailed from St. Catherines, Ontario. Can-Am historians among us will take note; one of Sadler's most successful design exercises was a mid-engined chassis that was the forerunner of what developed into the Can-Am racing series. Team McLaren's success in this program is said to owe much to Sadler's involvement, drivers McLaren and Hulme notwithstanding. Before the McLaren era in Can-Am, Sadler's own Chevrolet-powered specials blew the doors off the competition without discrimination. Sadler is rumored to be presently designing helicopters in the southwest United States.

The first piece of one inch square thin-wall tubing was cut, fittingly, on January 1 of 1959. Larger dimension tube ultimately proved unnecessary. Precious little of the front suspension on the Volvo was worth saving, so a 1948 Studebaker unit was pulled from a local boneyard. This was promptly lightened and outfitted with Gabriel shocks, which at With the chassis taking form, and receiving its front and rear ends, engine and trans, the anticipation was overwhelming, and the maiden voyage was performed before the body was attached. With open exhaust and a produce crate for a seat, the young men conducted tests on its driveability. At least, that may have been the official explanation. The center section of the body was constructed from aluminum sheet stock and lacks any compound curves. Meanwhile, in Davy's father's barn, the mold for the front and rear sections were being built using wooden bucks, chicken wire and burlap topped with a plaster finish coat. A body of nice lines, if not constant thickness. By spring of 1960, the car had been painted. "As young men, the real purpose of the car was not realized to any great extent due to extreme lack of funds, but the potential which Don and I saw in the car more than met our expectations," said Earle. "To give an idea of the financial condition of the time, Don was serving his body man's apprenticeship at 80 cents an hour, and I was still in high school when the car was begun. Don had $1000.00 invested in the project. It was very taxing indeed." The car was sold in 1962 to raise funds for Don's trip to England, where he found employment with the Merlin Car Company, a builder of formula car chassis.

In the ensuing years since the early '60s, adulthood set in, marriages had been solemnized and families were the things being built. Fraser Earle had a son, also named Fraser, who had an insatiable appetite for car facts. So much so that his nickname was "Specs," In this same year, after discussions with friends who fondly remembered the old car, the search commenced to locate the Davy Volvo Special. Ironically, one of the better leads that directed Earle to the location of the Special came from Don Davy himself, who heard that the original purchaser, a Mr. Ebel, still had the car. On following up this lead, it was found that Ebel had since died, but his widow was approached and the car was sold for the second time in its 38 years.

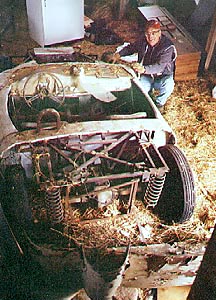

Earle wanted it. He had to want it very badly. Opening the door on the barn in Wiarton, Ontario, revealed what was left: A derelict mystery car in barn. $400.00 Canadian changed hands, and the car was loaded on the trailer and taken home to Mississauga.

In our next installment:

Photos courtesy of Fraser Earle

Easy-print version of this article |

the time seemed quite an extravagant expense! Next, a rack and pinion steering unit from a Morris Minor was adapted. The design of the Studebaker front end reveals unequal length A-arms sprung by a transverse leaf. The resemblance of this unit to any 1984 and newer Corvette is striking, except for the absence in the Stude's design of any rubber or urethane bushings. An added convenience was the fact that the early Volvo 2x9 brake shoes and backing plates appeared identical to the Studebaker. The finned brake drums came from a Mercedes. The rear suspension was adapted from the design employed on the PV.

the time seemed quite an extravagant expense! Next, a rack and pinion steering unit from a Morris Minor was adapted. The design of the Studebaker front end reveals unequal length A-arms sprung by a transverse leaf. The resemblance of this unit to any 1984 and newer Corvette is striking, except for the absence in the Stude's design of any rubber or urethane bushings. An added convenience was the fact that the early Volvo 2x9 brake shoes and backing plates appeared identical to the Studebaker. The finned brake drums came from a Mercedes. The rear suspension was adapted from the design employed on the PV.

an allusion to Fraser's penchant for specifications. The senior Earle often took young Fraser to vintage race events to show him the stage that consumed the (tongue-in-cheek) misspent youth of his Dad. The impression it left on this young man made him determined to convince his father that Earle should return in earnest to the hobby, and that it would be wonderful if this dream could be realized in the original Davy Volvo Special. In 1996, young Fraser Earle passed away at the age of 21, his life confiscated by muscular dystrophy.

an allusion to Fraser's penchant for specifications. The senior Earle often took young Fraser to vintage race events to show him the stage that consumed the (tongue-in-cheek) misspent youth of his Dad. The impression it left on this young man made him determined to convince his father that Earle should return in earnest to the hobby, and that it would be wonderful if this dream could be realized in the original Davy Volvo Special. In 1996, young Fraser Earle passed away at the age of 21, his life confiscated by muscular dystrophy.

It's the way all stories like this go: A body badly damaged. Repaired and damaged yet again. No motor or transmission. Frame rusted. A coat of straw and the dust of the ages. The original Michelin X tires still held air. Of curiosity was the 1966 Ontario trailer plate illegally attached to the rear of the car.

It's the way all stories like this go: A body badly damaged. Repaired and damaged yet again. No motor or transmission. Frame rusted. A coat of straw and the dust of the ages. The original Michelin X tires still held air. Of curiosity was the 1966 Ontario trailer plate illegally attached to the rear of the car.