|

|

|

Phil Singher editor@vclassics.com I've written before about our local Volvo "un-club." We're just a bunch of people who like owning old Volvos and happen to know (and like) one another. We don't hold any sorts of organized events, but we do have some unorganized ones -- I think it was Cameron Lovre who coined the term "Volvo socials" for these. A Volvo social consists of two or more of us getting together and doing something car related. Whoever shows up is free to help out whoever else needs it in doing whatever needs doing to whichever car needs it done. Or not -- it's pretty casual.

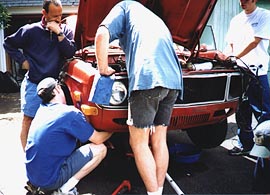

We had one of the biggest turnouts to date, with six or seven Amazons and several 1800s lining the curb. Note that there were no 140s -- the doomed car's major parts, in fact, are destined for Cam's PV444, including suspension, brakes, rear axle, Overdrive tranny, steering. . . Yes, we will report on this unlikely-sounding project as it develops. Don't start holding your breath anytime soon, though. Many of you know that, beginning in '70, Volvo produced a high-compression, big valve, fuel-injected B20 motor for use in the 1800E. This was the B20E: the most powerful non-turbo 4-cylinder Volvo motor of all. In '71, the B20E was available as an expensive option in the 140 series as well. In '72, for the North American market, it was succeeded by the B20F, which had less compression and power, so the B20E is comparatively rare and pretty much sought after. I wanted this one. Cam and I had checked out the car a few days earlier, tossed a battery in it and started it up. The FI system was ratty, but the motor itself sounded healthy, although absolutely covered in black, oily gook. We'd agreed in advance to work out some mutually acceptable deal between us; Cam didn't care if he kept the motor or not, and I could sure see it replacing the original B18 in my 1800S. By mid-morning of dismantling day, our resources for the job were on hand: two floor jacks, six jack stands, basic hand tools and lots of people. I envisioned the lack of an engine hoist presenting a problem, but Cam had an entirely unsuspected (by me, anyway) plan in his head. After maybe an hour, the radiator and driveshaft were out, and everything attaching the engine, transmission, steering gearbox and front brakes to the car was loose. We'd unbolt the whole front crossmember from the body, and lift the front of the car high enough to simply roll all that stuff out on its wheels as a unit.

Well, timing was problem number one -- Cam gradually advanced it from 10 degrees after TDC while I cranked the idle screw on the car's brand new Weber DGV out to keep the rev's at something approximating idle speed. Not that it wanted to keep running at idle -- I started cranking the idle mixture screw out as well. In about two minutes, we had it idling pretty well, although it was obvious the Weber was grossly misjetted, the valve adjustment was only halfway close and the throttle linkage wouldn't open the carb's secondary barrel at all. We explained what further work would need to be done, but we had other, more pressing problems at the moment. New guy was pretty happy with the improvement, even like it was. The prospect of picking up the nose of a 140 by hand soon removed any smugness we may (or may not) have felt from making the new guy's car run better, but the solution did eventually dawn on us: put the rear jack stands more towards the center of the car so the weight of the back end would help us out as much as possible. With some careful positioning and a lot of analysis about just which way things would shift when we hefted the front, we were soon able to pick up the front somewhat. The front would have to come way up, though, so a few trial runs showed that we'd have to take it in small stages. Four people would lift, while another two would notch the front jack stands up higher and higher. Even at that, considerable effort was required -- I guess none of us is exactly Mr. Universe. New guy had, somewhat unhelpfully, plopped himself down in the shade of the garage and was watching with some interest. As those of us participating gave one particularly red-faced heave, he casually asked, "Is that heavy?" The answer squeezed out through clenched teeth: "It's . . . a . . . CAR!" We had to set it down pretty fast that time. Fortunately, the pizza arrived about then, so we all got to take another break.

The remaining smaller bits and pieces of the car left quickly -- rear seat to one person (the fronts weren't worth saving), Overdrive logo and dash indicator to another (they'll look cool on his Amazon), windshield to a third (who wanted it for someone else's car), and so on. The parts that made up the car's fuel injection system went into the communal un-club stockpile. While that was going on, I took the tranny and bellhousing off the motor. We were, essentially, done for the day. Two days later, what remained of the car's body was hauled off on a flatbed truck, freeing up Cam's driveway. A few days after that, the motor arrived at my house in the back of a pickup, along with the transmission. My labor in overhauling the tranny would be payment for the motor -- not a bad deal, in my opinion; Cam will pay for whatever parts turn out to be needed, and he's in no hurry for it to be done. He's got a months of work to do on his 444 before even getting to stuff like drivetrains. Looking back, I have mixed feelings about the whole affair. Another old Volvo has met its demise, and old Volvos are not a renewable resource. It needed a lot of work and made for an obvious parts car, being well-suited to our various wants of the moment, but it could have been fixed up and made to be a good driver, too. It wasn't all that far gone -- if we'd found a 122S in similar condition, one of us would likely have bought it to restore, not dismantle. Many older models go through a stage of being just old cars before magically turning into classics. For 1800s, that period was short; for Amazons, the transition is nearly complete -- prices for both have risen sharply in the last few years, although certainly not to the level attained by other marques. In designing the 140, as Mark Hershoren aptly puts it, Volvo took the Amazon and "polished it until it glowed." There's irony inherent in sacrificing such a jewel -- even a rough one -- in support of what are, in the engineering sense, "lesser" Volvos. Of course, a few of our Volvos will be considerably less "lesser" as a result.

|

Recently, Cameron bought a '71 142E parts car which couldn't clutter his driveway for more than a few days -- space is tight in the older Portland neighborhoods, and he shares the driveway with neighbors. Anything that couldn't be taken off the car right away would go with it to the crusher. Volvo social at Cam's house, c'mon down!

Recently, Cameron bought a '71 142E parts car which couldn't clutter his driveway for more than a few days -- space is tight in the older Portland neighborhoods, and he shares the driveway with neighbors. Anything that couldn't be taken off the car right away would go with it to the crusher. Volvo social at Cam's house, c'mon down!

Uh, sure we would. Maybe now would be a good time to take a break and think things through -- or we could just call the hernia ward and make reservations right away. We opted for the break, just as an unfamiliar green 122S wagon cruised first up, and then back down the street, looking for parking. It did not sound a bit happy; in fact, it hollered at us painfully. Three of us went to take a look as a "new" guy climbed out. Cam called in an order for pizza and then followed, bearing a timing light.

Uh, sure we would. Maybe now would be a good time to take a break and think things through -- or we could just call the hernia ward and make reservations right away. We opted for the break, just as an unfamiliar green 122S wagon cruised first up, and then back down the street, looking for parking. It did not sound a bit happy; in fact, it hollered at us painfully. Three of us went to take a look as a "new" guy climbed out. Cam called in an order for pizza and then followed, bearing a timing light.

After we loaded up on a few carbos (or whatever weighlifters call eating pizza), the rest of it was easy. The car went up, the suspension, steering, motor and tranny (supported on a floor jack) rolled out, the car went down. Twenty minutes more work saw the rear end removed and set aside.

After we loaded up on a few carbos (or whatever weighlifters call eating pizza), the rest of it was easy. The car went up, the suspension, steering, motor and tranny (supported on a floor jack) rolled out, the car went down. Twenty minutes more work saw the rear end removed and set aside.